Today’s rude question: Is it possible that all the discussion of taxes in Washington is just distracting, meaningless piffle?

This question has bothered me for a really long time— over 15 years. It started to bother me when I wrote a column asking readers if they were tired of our stupid, complicated tax system. I asked if they would prefer something simple and universal like a national sales tax.

A few days later, the snail mail started coming in. It poured in. The mail room protested the volume of mail. They started delivering baskets of it. It came as postcards, as letters, as packages containing home screened T-shirts. When the flood subsided, we counted responses in the thousands and virtually everyone agreed— our tax system is ridiculous.

The reader response that started me wondering about meaningless piffle, however, was different. It was the print-out of a spreadsheet summarizing over 30 years of personal tax returns. The reader showed his gross income, his filing status, his exemptions and deductions and his final tax bill through marriage, buying a house, having children, and paying the last tuition bill.

Then, on the last line, he calculated the taxes he had paid as a percentage of his gross income. The result was amazing.

Through over 30 years of tax law changes big and small, through a large part of his adult life, through the intense inflation of the 1970s, through home refinancings and moves, his income taxes had averaged 10 percent— plus or minus 1 percentage point— of his gross income. His tax bill was nothing like the roller coaster you would expect from decades of political rhetoric and personal change.

Given the final bill it was clear that any time spent thinking or worrying about taxes was time wasted.

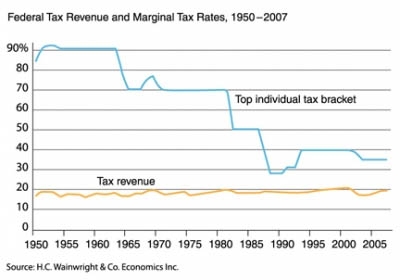

And it turns out to be the same for the entire country. For all the ups and downs of taxes, for all the fear and trembling that comes with each year that Congress meets and adds meaning to the famous quote from Mark Twain—“No man’s life, liberty, or property is safe while the legislature is in session.”— It remains that government tax revenue as a percentage of national output is remarkably stable.

The first person to observe this was an economist, W. Kurt Hauser. He noted in 1993 that while the maximum tax rate on income had been as high as 90 percent in 1950 down towards modern levels, government revenues from all sources were pretty much the same. They hovered around 19 percent of gross domestic product, except during severe recessions. (The current rate is about 15 percent of GDP according to government data but is expected to recover to 19 percent by fiscal year 2014.)

The flat revenue line led Hauser to suggest that there might be a practical limit for taxation, however it is devised, at around 20 percent of GDP.

Skeptics will find that the highest share of GDP ever collected in tax revenue was in 1944, when it hit 20.9 percent. It didn’t top 20 percent again for 56 years. In the year 2000 the top of a roaring bull market brought it to 20.6 percent of GDP.

Now, guess how much of GDP our government spent in fiscal 2010? Try 25 percent. Want to guess what the estimate is for the current fiscal year? Try 25 percent again. Much could be said about why the percentage is that high. We are recovering from a recession and the percentage will decline as output rises, etc. But the reality is that government spending as a percentage of GDP hasn’t been this high since World War II.

There is an important message here and it is very simple. Yes, we can raise taxes on the very rich. We probably should. We can also raise taxes on the near rich and the imagined rich. We can even raise taxes on the top 50 percent of the population, the people with incomes of at least $33,048 a year who already pay 97.3 percent of all income taxes. Doing that might make a small dent in the deficit problem.

Or not, given Hauser’s Law.

But whatever we do with the current tax system it won’t close the $1.4 trillion budget gap we face. The primary problem is spending. After that, let’s talk about creating a new tax system. The first requirement is that it should not drive us crazy.

On the web:

Federal Budget data, see Table 1.3

http://www.gpoaccess.gov/usbudget/fy11/hist.html

Hauser’s Law on Hoover Digest

http://www.hoover.org/publications/hoover-digest/article/5728

Graphic for website from Hoover Digest article above

This information is distributed for education purposes, and it is not to be construed as an offer, solicitation, recommendation, or endorsement of any particular security, product, or service.

Photo by Pixabay

(c) A. M. Universal, 2011